“Genomic selection totally revolutionised the world of breeding.” Sander de Roos, Global Director Genetics, and as such currently responsible for CRV’s global breeding activities, doesn’t hide his admiration. In the early stages, breeding values were calculated based on 3000 markers on the DNA. Today that figure has risen to 80,000. To enable reliable calculation of genomic breeding values, a reasonably sized reference population had to be built up first. A huge leap forward was made when the reference populations in various European countries were merged within the framework of the EuroGenomics partnership. This database now contains data on the performance of 1.6 million genotyped animals, including 40,000 daughter-proven bulls.

Doubling genetic progress, halving the number of bulls used for breeding and a huge upscaling. The idea of genomic selection, which came to fruition 20 years ago in the brain of a brilliant scientist, has revolutionised breeding.

Rising popularity of genomic bulls

Nowadays, genomic selection is part and parcel of daily breeding practice. In the Netherlands and Flanders, for example, around 72% of Holstein inseminations are done using semen from genomic bulls. In the last financial year, no information about the daughters of six of the ten most frequently used black-and-white bulls was known yet. In Flanders, that figure was even higher at eight out of ten. And in both countries, the most popular bull with breeders in the red-and-white segment was also a genomic bull (Delta Mauro). When it comes to using genomic bulls, dairy farmers in the Netherlands and Flanders are relatively cautious. In other countries more than 80% of the inseminations are done with semen of genomic bulls.

“Maybe the biggest gain from using genomic breeding values is that now we can effectively breed for traits with a relatively low degree of heritability, such as longevity, fertility and health” – Sander de Roos

Genetic progress doubled

“All farmers can profit from the benefits of genomic selection, including farmers who use only daughterproven bulls with high reliability”, de Roos says. “As genomic bulls are widely used as soon as they become available, there are large numbers of lactating daughters three years later. This immediately denotes highly reliable breeding values to these bulls”, he explains.

“The first daughters of today’s genomic bulls can be compared to the ‘second crop’ of the waiting bulls used back then”, according to de Roos.

However, faster breeding and sharper selection also entails a risk: inbreeding. Since the introduction of genomic selection, the degree of kinship in the Holstein population has risen at a faster rate, but the technique also offers opportunities to manage and control inbreeding.

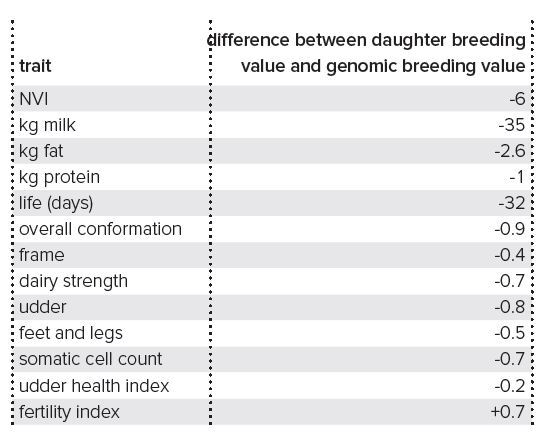

Genomic breeding values a good estimate

Do young bulls live up to the promise of their high genomic breeding values? This was a much-asked question in practical circles when genomic selection was introduced. To answer this question, Gerben de Jong analysed the figures of the 738 bulls who were assigned a breeding value over the last five years based on the performance of their daughters. He compared the analysis with the last genomic breeding values of these bulls. Table 1 shows the analysis results. “On average, bulls drop by six points in the NVI when their daughters start to lactate”, states de Jong. “That difference is relatively small and that also applies to the other breeding values for production, conformation, longevity and health. On average, genomic breeding values represent a good estimate of the genetic predisposition of bulls”, he concludes. “The breeding value of genomic bulls averages 100 points NVI higher than the value of daughter-proven bulls. Even with a drop of six points, that is still a large difference. This means that farmers who use semen from genomic bulls will improve the genetic level of their herd faster.”

Genomic bulls higher, daughter-proven bulls more stable

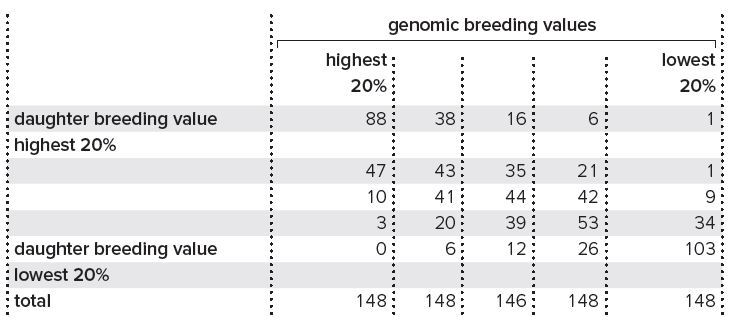

However, what is more important than the average is the deviations of individual bulls. “No one wants a high scoring genomic bull that fails to deliver on the expectations. But the opposite also applies: it is a shame when a bull full of potential is only identified when his daughters are lactating”, de Jong explains. To gain a better understanding of the deviating figures for individual bulls, he divided the same 738 bulls into five groups based on their genomic breeding value for NVI. He then made the same distribution based on the breeding value derived from data on the bulls’ daughters.

Table 2 shows the analysis results. Of the 148 bulls whose breeding value placed them in the upper 20%, 88 (59%) also ranked among the best 20% based on their daughter-proven breeding value and 47 (32%) were placed in the category just below. Conversely, 70% of the lowest scoring bulls were correctly estimated to have limited breeding value based on their genomic breeding values. The figures clearly reveal that, ten years after their introduction, genomic breeding values are a good estimation of the genetic predisposition of bulls But the same figures also show that genomic breeding values are not an absolute truth; there will always be some bulls who disappoint or exceed the expectations. “So the advice given to farmers to spread their choices when using genomic bulls still stands”, says de Jong.

Calves genotyped by 2500 farmers

A second revolution, that we are actually at the heart of today, is genomic selection being applied by farmers to their own herds. More than 2500 dairy farmers in the Netherlands and Flanders currently use this service. This means that around 100,000 calves are genotyped annually.

Unlimited possibilities

Sander de Roos also predicts that genomic testing will increasing become standard practice. “I think that ultimately it will be just as normal as herdbook registration”. “With genomic data, farmers have a way of achieving much faster genetic progress in their own herds and according to their own breeding goals. Genome data enables reliable selection of the animals used for breeding. Combined with using sexed semen to inseminate the highest ranked animals and beef bull semen for lower ranked herd members, this will give another boost to the pace of genetic progress.” The revolution that started ten years ago has not stopped yet.